Jesus in my knapsack

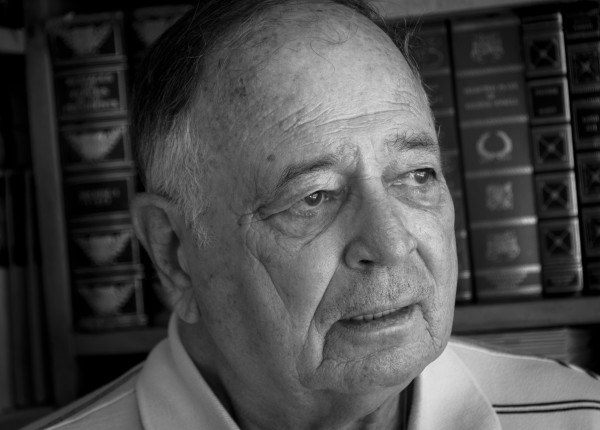

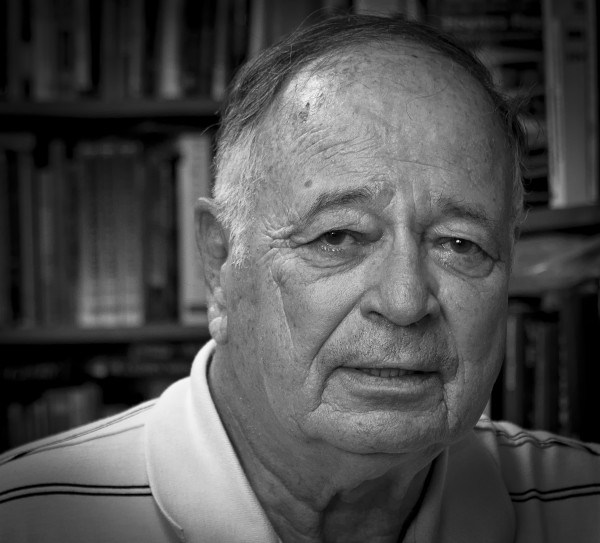

Lawrence Egan is fluent in Spanish but his Queens, New York, accent still comes through. His second-generation Irish father was not enthused about Larry becoming a priest. He became decidedly less enthused when Egan told his parents he had signed up to be a Maryknoll missionary.

Father Egan arrived in Guatemala in 1964, just as the anti-government revolutionary movement was beginning and as the government was increasing its brutal reaction. While Egan was trying to help Maya Indians in the hills of western Guatemala, the government began to bomb their villages in the eastern regions trying to suppress the guerrillas, many of who were ex-military and former government officials.

By the time he transferred to El Salvador in 1967, observers estimated between 3,000 and 8,000 Guatemalans were killed. It was only the beginning of what would become known as The Silent Holocaust.

He recently published “Maryknoll in Central America, 1943–2011” which chronicles the difficult work of Maryknoll personnel to navigate the treacherous paths through the jungles of politics, ethnic struggles and Catholic church policy.

He left the priesthood in 1977, married a former Maryknoll Sister and came to Colorado where he worked in bilingual education for the Colorado State Department of Education.

In 1991 went to Vietnam, and later Myanmar (Burma) to serve as the Country Director for International Development Enterprise (IDE), a non-governmental organization specializing in the transfer of low-cost technology to developing countries.

Since 1999, he has owned a bookstore in Littleton called ABBS VOLUME I, where his book is for sale (303-347-9460).

TRIBUTARY

Your first parish was in Guatemala in the western highlands at Huehuetenango. What was it like?

EGAN

It was the end of the line. We were on the border with Mexico. We had no electricity except for a small generator, which we used for a short time at night. There were no health services and no schools. But I was 26 so it was an adventure.

Our parish was made up both of Maya Indians and Ladinos. Ladinos are a socio-ethnic category of Mestizo or hispanicized people. The Indians speak a native language, wear traditional Maya clothing, many without shoes. Ladinos speak Spanish, do not wear Maya dress and can afford shoes.

The Ladinos exercise economic and political control at all levels of government throughout the country. They are the townspeople. The Maya are subsistence farmers. They exist on a daily diet of corn and beans. They were mostly illiterate.

For the Maya, religion was a vital part of their everyday life. The Ladinos were what we called cultural Catholics who for the most part appeared for baptisms and Holy Week and not much else.

The Maya were already baptized Catholics but the in some of the villages practiced “la costumbre” a mixture of folk Catholicism and pre-Columbian Maya rites. They had their own “chimanes” or shamans, who were part healers and part religious leaders. As you would expect there was some antagonism between the established shamans and us as new priests. We had some compromising to do in order to coexist. It was an old conflict dating to the Spanish Conquistadores. The farther away the villages were from the central towns, the more traditional was the religion.

TRIBUTARY

The chimanes could have stopped you in your tracks if you had not been careful.

EGAN

One of the new ideas that came out of Vatican II was that the “seed of God’s word was already present in cultures before the coming of Christianity.” This caused missionaries, professors and church leaders to question the need to challenge the beliefs, practices and understanding of the indigenous people. So we adapted. The U.S. model for how the church works could not have succeeded in this setting. We learned from each other and found common ground, even friendships.

I went with Jesus in my knapsack to give Him to the people but I discovered he had already beaten me there and he was a different Jesus than I knew — the Jesus of the poor and dispossessed.

TRIBUTARY

You spoke Spanish but the Maya didn’t. How did you overcome the language barrier?

EGAN

Each village had Mayan lay people who were all volunteers and they basically did all the teaching. They knew everyone and they knew who was more Catholic or more costumbre.

I tried to visit each village once a month. Our area had 10 villages, five of which had to be reached by horse or donkey. I would say Mass, teach and help the local lay people with daily routines. Some of the Maya within the parish spoke Spanish so we would teach them and they would teach others. We had to use the local people as translators until we got better with the native language.

We were also training, and empowering, local parishioners to be lay ministers who would assume roles such as administering communion, preaching and baptisms, tasks that had been reserved for us as priests.

At the same time the church began the development of central training centers where people could come for courses in agriculture, basic adult education, community development and leadership training. It also stressed the role of women. From this gradually developed a number of Maya political activists who got involved in local elections.

TRIBUTARY

So the Maya were beginning to feel respected, the chimanes were tolerant and some of your American coworkers were adapting to these new ideas. Was the government supportive of this work?

EGAN

The Catholic Church for years before then was perceived as a key government ally. The Maya didn’t trust the Ladinos, the government, and by association, some of us. So that was one factor.

In 1960, a group of junior military officers pulled an attempted coup that failed. They went into hiding and this became the nucleus of the forces that would fight the increasingly autocratic government rule. By the time I arrived (1964) the movement was growing but it did not include the Maya.

From 1966 to 1968 the government forces, led by Col. Carlos Arana Osorio, carried out the brutal killing of around 8,000 peasants in order to eliminate 100 to 500 rebels. For years the government tried to maintain the status quo and was suspicious of any groups that organized people. They labeled the insurgents as communists and declared a crusade to promote the “survival of Western Christian civilization.”

In reality it became genocide. The military began to perceive the Catholic Church as the enemy because so many church workers stood with the Maya, defending their rights to land and life. Many native priests and thousands of church workers were killed. During this period more than 200,000 Guatemalans were killed, 90 percent at the hands of the military.

TRIBURARY

It sounds like what started as a modest effort to encourage the poor turned into a nightmare.

EGAN

The Church had been moving gradually away from its role as an indirect supporter of the established power groups to a role as the voice of the voiceless. The government started accusing us of being “involved in politics” but the church had been in politics for 400 years. But now we were changing sides.

This cost many of our friends their lives. The lay leaders who we had been training became prime targets for the death squads. Many would give valiant service in the midst of genocide. They truly were the unsung heroes of that terrible time.

TRIBUTARY

Isn’t this ethnic and political pattern of conflict being repeated time and again all over the world, even now in the Middle East?

EGAN

That’s true and the moral decisions for the missionaries, the church and the non-governmental organizations are being repeated too. Does one support a revolutionary movement with all its faults and excesses against a clearly unjust government in the process of persecuting its own citizens? What are your options?

Active nonviolent resistance when faced with entrenched military dictatorships is one option. Armed resistance, or active support of the opposition is the other. And even if you choose nonviolence, as we did in Central America that will not stop the government from making church workers their main opponents. Non-violent resistance is still resistance. The problem is you are a foreigner in someone else’s country and that only complicates matters.

The best presentation of the nonviolent option is Tom Melville’s biography of Fr. Ronald W. Hennessey, “Through a Glass Darkly: The U.S. Holocaust in Central America.”

TRIBUTARY

You were transferred to El Salvador in 1967 and spent five years there. Were the conditions similar?

Yes and no. I went from the mountains of Guatemala to an upper middle class parish where 60 percent of the men had a college education, many educated in the United States, and all the women had a high school education. The community wanted American priests and there weren’t any in San Salvador (the capital of El Salvador) at the time.

Here it was not Maya against Ladinos. It was poor against the rich and middle class. The government was military-run like Guatemala, and it was also the peasants who were massacred by the troops. And also similar, there might have been 50 or 100 guerillas in the area but thousands of the locals were killed in the attempt to get at the resistance fighters.

We took this parish because we felt the president of El Salvador might come out of this parish someday. These were the people who eventually would be running the country at various levels and if you wanted to see change you had to work with them.

TRIBUTARY

Why did you leave the priesthood?

EGAN

Well celibacy when you are in a place like Central America with all this stuff going on, not being married is a plus. You don’t have to think about family. But when you are back in New York at a desk job, celibacy has less appeal.

Book by Lawrence Egan

RELATED LINKS

See the film online: June 29, 2012 – July 28, 2012 Watch now »

Film

Film

QUESTIONS FOR READERS

1. How aware were you of the civil wars in Guatemala and El Salvador in the 1970s?

2. Have you ever thought of being a missionary?

Please respond using the Share your thoughts section below.

SUPPORTING TRIBUTARY

- Opt in. If you enjoy our work, opt in by giving us your email. This simplifies the notification effort for the next edition. No fees. Total privacy.

- Please share this article with your friends. Word of mouth is our most reliable resource.