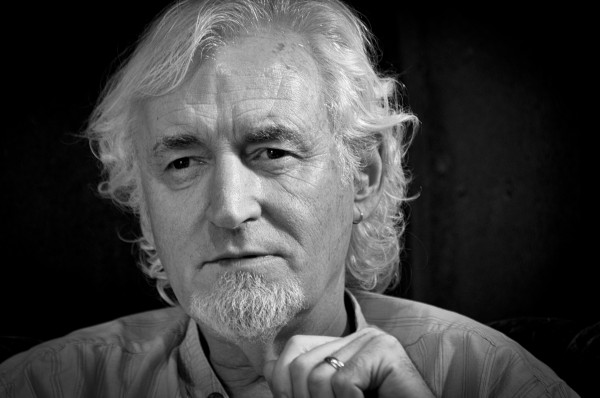

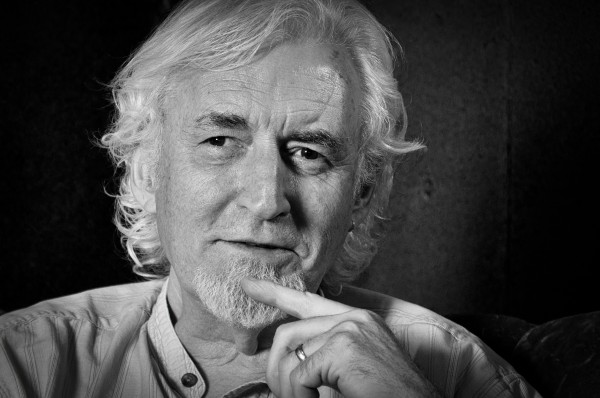

An Irish Storyteller

In the town of Ballybay, in the County of Monaghan, four roads converge beside Lough Mór. The Dromore River meanders south of this Irish town. Tommy Makem, The Godfather of Irish Music, sang about a young lass in Ballybay who had a wooden leg to which she tied a string and played it like a fiddle.

Along Clones Road sat an old nursing home where another storyteller was born in 1951. A nun wrapped the infant, Mick Bolger, in a blanket and placing her hand on his head, whispered a prayer in Gaelic that the Lord would guide his steps.

Mick listened to many stories over the years in the places where Irish stories are shared; living rooms of neighbors, on the bus to school and later in the pubs. The Irish would call him a seanchaí (pronounced shan-a-kee), a teller of Irish stories. He ended up marrying a lass who played the fiddle and together they developed Colcannon, an Irish group that artfully weaves traditional Irish music with their own tunes and of course Mick’s endless stories.

Formed in 1984 in Boulder, Colorado, Colcannon has released eight CDs encompassing various forms of Irish music on the Oxford Road Records label in Denver. The band’s recent CD, The Pooka and the Fiddler, is a story by Mick Bolger with original music by Colcannon which received the Parent’s Choice Award for artistic merit from the Parent’s Choice Foundation.

The Emmy®-award-winning PBS special, “Colcannon in Concert,” filmed at the Denver Center for the Performing Arts has aired nationwide. Colcannon was named ensemble-in-residence at Colorado College, the first non-classical Irish music group to be awarded this position.

TRIBUTARY

It seems like you love to hear stories as well as tell them. Where did you start hearing the old stories?

BOLGER

When I was a kid there were certain houses in every neighborhood that were known as cèilidh (pronounced kay-lee) houses. Cèilidh has to do with the notion of coming together. It was a place where people would drop in and socialize. In the evenings, neighbors would just walk in, no knocking on the door. Knocking was kind of rude. They would have a cup of tea and chat, share stories and sing songs. Stories about local lore. I loved to just sit and listen. Even in high school, the songs were around. If we went somewhere on the school bus a lot of that singing would go on. Everybody just knew the old songs. And a lot of these songs were the ones I sang when Colcannon first formed.

TRIBUTARY

Irish lore ascribes the talent of the seanchai as av gift from a higher power, maybe even from the fairies.

BOLGER (Laughing)

There’s certainly a tradition of thinking of music in Irish terms as not so much composing it as almost channeling it. That if you listen in the right places and at the right times, tunes will be given to you. It’s not a way of apply knowledge to construct something but applying a knowledge to gather it in. And there is a feeling that having done that, it really doesn’t belong to you. It was given and you were the receptacle. That’s how we feel in Colcannon as a group. It’s an odd sort of situation, like being in a céllí house, it’s not competitive and it’s not show-offy. None of us is interested in geewhizzery where people are saying, “Wow what great players.”

What we would like to hear is, “Wow what a great tune.” And we try and mix it up so that one song has you in tears one minute and the next song has you laughing, next one feeling something dramatic, and the next one more reflective just as an evening in somebody’s house. Nobody there is showing off and everyone is contributing to that atmosphere. And their storytelling is about stuff that happened to them or people they know or stories about places round about. They pass them on. Certain stories belong to a certain geography. Or a song that someone sang at a funeral that everyone remembers.

So the storytelling is not separate in any way from the people. And when one tells a story another might top it off with a quip. And it’s all very unselfconscious. If you want to learn more about this read “Passing the Time in Ballymenone,” by Henry Glassie He lived in one area of Ireland for a number of years and closely observed the social interactions. It’s basically anthropology. How the culture worked. It is absolutely fascinating. How conversation works between Irish people.

TRIBUTARY

Does your music do that, or is it the story set to music. Do you attempt to make music move around like an Irish conversation?

BOLGER

Irish tunes are very short. They are also very simple and repetitious. They are good for dancing that way. What happens is we will go through a tune several times but we will make slight little variations on it. After a while even a simple tune will be repetitious. So what we do is go into another one. We will do a medley of two or three tunes. We will know because we have it all worked out. To find the variation in the first tune and then find the next tune that will fit in with it takes a lot of work. So we definitely try to create variations and take the crowd to a sad place and then to a happy place.

TRIBUTARY

Sort of an extended story. A journey to many places.

BOLGER

The Irish appreciate a good story well told. They are very verbal people. I think there is something very therapeutic about stories. It involves a journey with many experiences and that gives one power. The idea of theater is that we can vicariously experience somebody else’s life. By being able to experience that, and stay removed from it, it’s not actually real anyway, it does evoke the emotions. By going through that process it helps to heal us and give us power in those situations where we may feel powerless.

A lot of the songs that I like are either funny, bawdy or really sad and personal. I think there is an event that happens here that is at the core of storytelling. It is a way of developing skills to deal with shock, grief, torture, love… so that when they come up in real life you are better able to handle that. Stories take us through emotional occurrences that allow us to handle those situations.

I remember a quote from Oscar Wilde: “A sentimentalist is simply one who desires to have the luxury of an emotion without paying for it.”

Stories also take us away from that dreadful loneliness that surrounds us. Loneliness is probably the very worst human affliction. I think it is why we are so terribly afraid of death. And storytelling helps us feel that we are not alone and not disconnected. We are not so powerless.

TRIBUTARY

What brought you to the U.S.?

BOLGER

Ireland was very Catholic, very paternalistic. There were all kinds of authorities to obey and your best hope if you stayed was to become one of those authorities that other people obeyed. The limitations of that were terribly galling to someone who is 17 years old. I was expected to go into the priesthood or get a good job in civil service or go onto university but pretty much you were tracked toward a certain type of life. None of that appealed to me.

I was very lucky because I escaped the political troubles. Some of my brothers were pressured to join the IRA, pressure that they resisted. (Mick has four brothers and three sisters and he is the oldest). My mother was threatened by the IRA because we lived right on the border between northern and southern Ireland. It would be the border between County Donegal and County Tyrone. This is a political boundary, not religious. Twenty-six of the counties are known as the Republic of Ireland and are independent from Britain. Six of the counties are known as Northern Ireland and are British, part of the United Kingdom.

The rallying call at the time was “One man. One vote”. You had to own a house in Northern Ireland to be able to vote. But if you were in a Protestant area, no one would sell to Catholics, so the Catholics didn’t have votes. So it started out as a civil rights issue around voting but it quickly reverted to the old conflicts of a united Ireland versus a northern province that wanted to stay British.

In the mid-1960s I was sent to a secondary boarding school near Dublin taught by Franciscan priests. Just about the time I finished school in 1969 was about the time of the beginning of The Troubles. Riots had started in Derry. This was about 10 miles from where my family was living in Donegal. By Sept. 1969, I had found work in England in construction and left.

With the money I earned working in England I traveled abroad for while. I was a hippie at the time. I was just a kid trying to see what was going on the world. I spent six months in Portugal making horseshoe nail jewelry and selling it on the streets.

Then I went back to England and decided to go to the University of Lancaster. There were a lot of American students there from the University of Colorado in Boulder who spent their junior year abroad studying at Lancaster. And every year the University of Colorado offered a scholarship to graduating Lancaster students to come and spend a year in the U.S. that I applied for and received. So I came over here (1979) and have pretty much been here ever since.

I became a citizen in 2011. I’m not sure why I didn’t do it earlier. I think part of me has never taken my coat off in America. Even now at the age of 60, some part of me thinks, well when I’ve gone through this phase, I’ll go back to Ireland and make something of myself.

TRIBUTARY

How did Colcannon come about?

BOLGER

Somebody told me about this pub in Boulder, the James Pub and Grill, where they had Irish music on a Monday night. The pub in Ireland is much different than the bar in the U.S. It’s like the communal living room. People meet and chat and tell jokes and have a drink. And it may be a lot warmer than your own house in the winter. Basically, I was hoping it would be akin to something that I was used to. And there were musicians there, wouldn’t you know. I started hanging out with the musicians and would sing the occasional song or tell a story. But it turned out I knew a lot more traditional Irish songs than anybody else.

So I would sing with different small groups and met other musicians and gradually Colcannon got formed. Then in 1984, the James had an opening for a regular house band. So we became the house band for nearly nine years, mostly on weekends. By 1991 we were making our first CD in a big studio with a proper producer. And by then we were writing our own music. We were still firmly based in Irish traditional music but we were moving away from what would be expected from a pub band that would be more of the Clancy Brothers songs.

TRIBUTARY

And the storytelling continues through Colcannon with or without vocals.

BOLGER

Absolutely. That’s what human beings do. Storytelling. We spend our lives talking and telling stories. When we’ve taken care of shelter and food and reproduction that’s what we do next. Storytelling is what the human condition is about. I would say that we put roofs over our heads and get food so that we can do this.

________________

The seanchai If you stand beside the big Oak tree early in the morning, and wait for the warm fingers of the sun to lift the mist from the valley floor, you will see the place where I was born. So long ago, that people forget that there was such a time. It was a day like any other, the warm sun creating little wisps of moist air, reflecting all the colours of the world around the cottage as I took my first breath. It was also the day, my mother told me, the fairies came. They laid their hands on my head and said that I was blessed, and I would keep their history in my head and tell it wherever I was to travel. So gather round, listen, for I am the seanchai. — by John W. Kelley ____________________RELATED LINKS